***The following is an excerpt from the blog posts that cover Titian’s Venus of Urbino. As a result, some of what follows won’t make much sense - not unless you’ve read the other entries. But if you stick with it, you will get the gist of what the painting’s about.***

Man of Mystery

Giorgione’s a peculiar fellow. His paintings are a slow burn. It takes a while to get used to them. But everyone who spares them the time falls in love. This is probably why he’s one of the most celebrated artists of the Renaissance. In spite of all the affection though, we know next to nothing of the man. From his nickname, Zorzi (Big George), we imagine he was a burly bloke. We know a little about his training. We’re confident he hung out with a literary crowd and enjoyed books. But after that, we’re down to whispers and glimpses. We can’t even agree on his catalogue. Of the dozens of works associated with his name, only a few are certain. Even so, this handful has been enough to assure his reputation as a thoughtful, poetic painter whose pictures ooze mystery and otherworldliness.

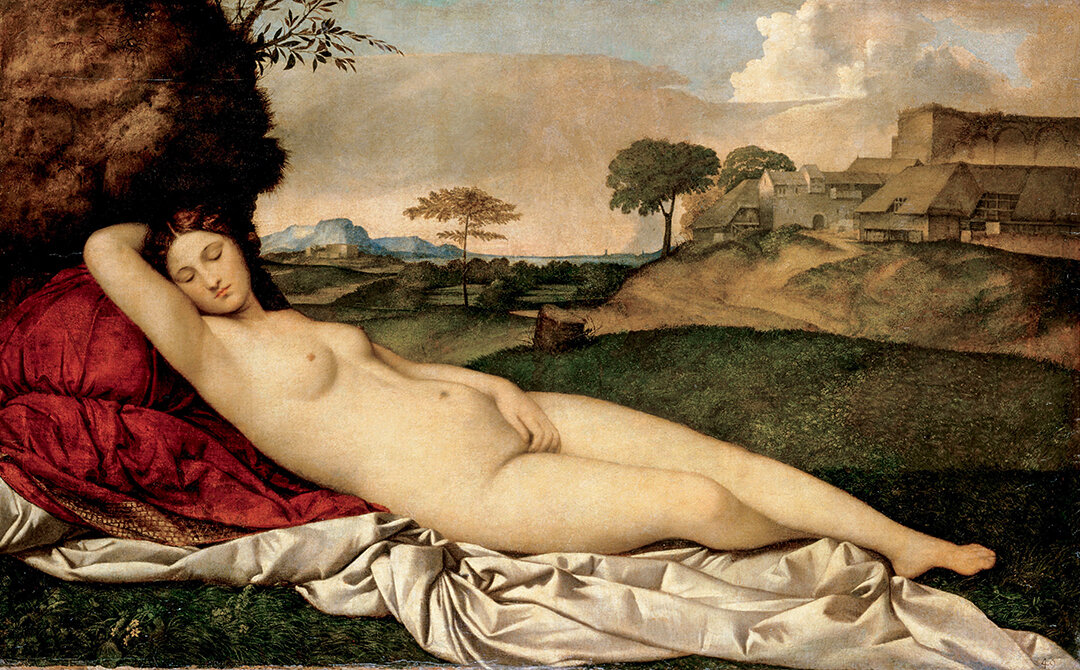

He and Titian were contemporaries. While they were young men, they rubbed shoulders (uneasily, we think) on shared projects such as the frescoes commissioned by the German merchants of Venice for their headquarters. As is occasionally the case when great talents go head to head, each matched the other so intensely that it’s sometimes impossible to tell which of the pair painted what. The issue’s made thornier by rumours that Titian, after Giorgione died of plague in his early thirties, completed some of his peer’s unfinished works. One of these was a dreamy nude slumbering in a landscape. She’s called the Sleeping Venus. She’s kept these days in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. And it’s obvious where Giorgione got the idea for her. She’s a dead ringer for the figure in the HP woodcut. Just as Titian’s Venus, painted 20 years later, is a dead ringer for Giorgione’s, right down to the wandering hand. What we have here, then, is three generations in the same family. The Venus of Urbino is the grandchild. If we’re going to understand her properly, we should try to work out what was going on in Giorgione’s mind when he painted her predecessor, and how the HP Venus might have influenced him. We’ll return briefly to the book.

The story in HP, such as it is, unfolds at the pace of molasses running up a hill. Poliphilo’s usually too busy frothing over buildings to move his threadbare tale along. This means that when something important happens, it stands out starkly. There’s one incident which is especially climactic. As Giorgione flicked through the pages from which he nicked his nude, it would have jumped out at him. It’s worth retelling. It’s the moment when Poliphilo – having made zero progress in his quest to find Polia - decides to follow the path of Venus. His fruitless wanderings have brought him to three gates carved into a mountain face. They each open into a unique realm where different values hold sway. Only one will lead to Polia. Poliphilo must choose correctly by meeting briefly with the individual gatekeepers behind each entrance. These are a trio of women. The first is a drab, pious crone representing a Godly life. Poliphilo isn’t at all keen on this, and steps back. The second is a fierce and muscular lady brandishing a sword. She stands for earthly effort and glory. This is an improvement, but likewise doesn’t appeal greatly to our man. The third is a noble and seductive temptress. She represents the Mother of Love or Venus. Poliphilo’s much cheerier about this option. He steps through the portal and it closes behind him. Instantly, things look up. A gang of sassy bare-breasted nymphs gather round and grind against him provocatively. Just as the teasing reaches boiling point and Poliphilo totters deliriously at the edge of reason, they dash off again. Then, a few lines later, Polia approaches. Although it takes a little while for her to be recognised by her beau, the couple are at last united. More nymphs turn up to initiate them into the rites of love in a temple dedicated to Venus. Joy and celebrations abound. Of course, a little later, poor Poliphilo wakes up and realises it was all a dream. As endings go, it’s a bit of a downer. But a number of messages have been transmitted loud and clear. Prominent amongst them is that when it comes to the deepest forms of human fulfilment, Venus pays out much better than earthly glory. Or even God.

Layabout

This recasting of Venus as a more powerful figure than normal repeats throughout the book. She’s never presented to us in her usual role as a mere goddess of love. She’s always greater and more nourishing than that. She’s called – and the distinction is important - the mother of love. The idea is ramped up at the temple to which Poliphilo and Polia are brought. It’s described as the temple of Venus Physizoe: Venus, source of all life in nature. In fact, if we go back to the woodcut of the nude carved into the fountain, we can spot underneath it – as Giorgione doubtless did - a Greek inscription which reads Panton Tokadi: the mother of all. Taken together, these titles point to a vastly more substantial deity than the one we imagine hovering around besotted couples and bedrooms. Hypnerotomachia Poliphili transformed Venus into the ultimate feminine godhead from which everything worthwhile is born.

The characterisation was unusual. But it wasn’t brand new. In his poem De Rarum Natura, the Roman writer Lucretius was the first to play around with the concept of Venus as a supreme generative figure. He didn’t think of her as a personality though. He was sceptical of the existence of gods. He felt she was a principle rather than an entity. If she could be said to exist at all, it was as a symbolic embodiment of reproduction. Ovid, who came after him, had slightly different notions. But again, he was poet with no time for something so minor as a goddess of love. He was more interested in the idea of Venus as a generating force. In his Fasti , he cast her as the prime mover who created things as fundamental as the sky, the earth and the seas. Our Roman friends even had a phrase for the goddess in this role: Venus genetrix omnium (creator of all). Both poets were popular in book-loving Venice. Lucretius in particular was the subject of much chatter among the chin-stroking library-lovers of Giorgione’s time. Finding a repetition of the ideas touted by the antique poets, while he pondered the reclining nude he was about to kidnap from HP, was probably all the inspiration the painter needed. He would depict Venus less as a god of love, and more as a giver of life. We better see how he did it.

Home On The Hill

Most people, when they look at the Sleeping Venus, are drawn immediately to the long stretched out figure that occupies the front of the canvas. And anyone who’s read this far, will instantly zone in on the familiar sight of wayward fingers exploring forbidden places. But before we try to understand events between the thighs, we’ll have a look at the landscape. This is where Giorgione does a lot of heavy lifting in terms of his message. On the right, we can see a number of buildings. They’ve been painted large enough to dominate their quarter of the picture. This means they’re important. If we zoom in on them, we quickly spot a handsomely proportioned stone manor house sitting tidily on the hilltop. It’s in good repair with a sturdy balcony overlooking the landscape. A number of buildings cluster around it. These are made from wood. Thanks to their broad low entrances and the timberwork visible on their sides, we can tell that they are the barns where the harvest is stored. And they’re massive. They utterly dwarf the manor house. It’s as if a gang of hulking aircraft carriers were moored around a yacht. Of course, we expect barns to be larger than houses. But these are exceptional. Giorgione’s gone to great lengths to make their scale unmissable. The message is plain. The landscape the sleeping Venus presides over is one of extraordinary abundance. The harvests are so bountiful they can only be housed in a series of gargantuan outhouses.

An Unexpected Appearance

It’s not just the buildings that tell this tale. To the left are a pair of rich green fields bounded by rows of trees. It’s no barren wilderness out there. The land is productive. Further beyond, a broad lake stretches into the distance. There will never be a drought or a shortage if a well dries up. If we look closely at the distant shore that lies beyond the lake, we can make out a pair of tower-like buildings. If we look closer still, we discover one of these (possibly both) appears to be a windmill. This is a very telling inclusion. Windmills simply don’t feature in Italian paintings of the time. At all. If Giorgione decided to introduce something so abnormal, it can only be because it was vital to the picture’s overall theme. The obvious conclusion is that he wanted his audience to think of crops that need grinding, such as olives and wheat. Implying their presence with an unusual but easily recognised structure was a cunning move. It meant he could skip the clumsier task of painting muddy grey olive groves and loud yellow wheat fields without losing any of the message. It’s a lovely piece of inventiveness.

A windmill isn’t the only uncharacteristic thing to show up in the picture. If we return to the settlement on the hill, high above the 16th century buildings are the remnants of an antique classical edifice. This is interesting. Ancient architecture doesn’t occur in Giorgione’s works. He liked to keep things contemporary with his own time. So it’s a safe bet there’s an implication here. If we squint closer, we find the structure is overgrown and collapsed in places. Even so, its ramparts soar imposingly over the homestead built at its base. Not only does this point to the ancient world Venus comes from and how it looms large over the present, it’s surely the case that the manor house was fashioned from stone which fell from those archaic parapets. The old has given birth to the new, and even now coexists with it.

It’s worth looking at the foliage around the picture too. Trees are prominent. Particularly the two that occupy the middle third of the canvas. These have been painted so as to stand out strongly against the sky. Giorgione wants them to be noticed. (We’ll come back to this pair in a few moments; they’ve a crucial role in what follows.) He’s done the same with the plant growth atop the knoll behind the goddess. This is unmistakably a small bay tree – many will know it as laurel - the leaves of which were traditionally part of the crowns the ancients dished out for special achievements and victories. Giorgione deploys it over Venus’ head in a natural and unforced way. He mightn’t have her wearing a wreath, but he nonetheless suggests the goddess before us is a triumphant figure. He honours her. He shows us she’s supreme.

. . . Of All She Surveys

All these references are intriguing enough in their own right. But the allusions to crops and trees catch the eye. They tie in neatly with a line in Ovid’s Fasti, where he credits Venus for the existence of both. He even mentions how grass grows under her watch, something we see echoed in the intense, lush greenery sprouting below and behind the goddess. Grass never appears in such overwhelming quantities in any of Giorgione’s other pieces, most of which sport terrain made up of dusty, packed earth dotted with shrubs. We’re looking at a deliberate effort to mirror the Roman poet’s thoughts as closely as possible. And it’s relentless. Everywhere we look we find the signs. The entire landscape from front to back is churning out the goods. It’s an earthly Eden. Venus lies in front of it. The slumbering queen on her gilt edged fabrics. Beautiful, unconquerable and generous. The mother of all we see.

Now we’ve a rough idea of the theme of Giorgione’s background, we can turn to the elephant in the room: those fingers curling into intimate places. How are we to reconcile them with what we’ve discovered in the rest of the picture? If we borrow the centrefold notions the Pinups put forward to explain Titian’s Venus, it’s obvious they just don’t fit with what Giorgione’s painted. The same can be said for the big idea proposed by the Babymakers. Both groups believe the fingers are servicing human needs like pleasure and conception. What possible justification could there be for either here? There isn’t one. We’re looking at a divine giver of life. She’s not a centrefold fumbling for kicks. And she’s certainly not a demonstration of how a young bride might conceive with a wham-bam lover. She’s far grander than that. No. If the hand signals anything, it’s Venus’ abundance. Giorgione’s planted her fingers between the loins to alerts us to her generative power, and the feminine spring from which her bounty emerges. He’s painting her as the cosmic mother we find in Ovid, Lucretius and HP. It’s risky stuff, to be sure. But if the hand was placed anywhere else, even as little as an inch or two more modestly to the side, the message would be lost. Granted, it may be a tall order to understand any of it at first. For most of us, a gesture of this kind can only have a sexual connotation. But the painting wasn’t meant for us. It was for someone else. Someone who had a set of reference points a long way from our own.

This was a man called Girolamo Marcello. In his youth, he was something of a 007 character. He was sophisticated, came from a good background, was armed with a ready supply of cash, and had a patriotic taste for espionage. As a well-connected young merchant, he’d been booted out of Constantinople by the Ottomans for spying, and had to return to his hometown of Venice. But there was no disgrace in the setback. Girolamo kept a fine house, a shining reputation, and was awarded high offices. He also enjoyed the company of the same literary set as Giorgione. The ideas and books we’ve encountered would have been familiar territory for him. With common interests like these, the former spy and the artist got on well enough that Girolamo bought three pieces from Giorgione. The third and last of these was The Sleeping Venus, which was commissioned a couple of years before the painter died of plague.

During the Renaissance, it was often the case that a patron who did repeat business with an artist would have an intellectual connection with them. Especially if their literary tastes overlapped. So, we’re not looking at a situation where a wealthy dimwit lobbed cash at a painter for whatever he had in stock that matched the dining room wallpaper. This was a meeting of educated equals. Undoubtedly, they’d have discussed the picture in advance. The Venus before us is the synthesis of both their well-lettered imaginations. Given the rarefied books these men dipped in and out of, we shouldn’t be surprised if her gesture signifies something more elevated than base biological activities. It’s also worth pointing out that Venus had a special relevance for Girolamo. His family claimed they were descended from her through the Trojan hero Aeneas. It would be an odd thing indeed to request a picture of great-great-granny interfering with herself. She wasn’t a gynaecological manual. She wasn’t a pleasure seeking hussy either. She was a totem for the Marcello family lineage. And the concept of lineage, as we’re about to see, is central to the painting. Literally.

Prime Location

There’s something wonderfully odd about the way Giorgione’s composed the picture. He’s chosen to place a hum-drum tree stump at the precise centre of the canvas. This is an unexpected move. Giorgione normally avoids geometric devices in his paintings. He prefers designs that are more natural. But the stump’s conspicuous location does have an advantage: it’s a great way of telling the viewer it’s important. To help get this across, Giorgione also isolates it. There’s nothing close enough to distract from its centrality. This is the pictorial equivalent of erecting a lone radio mast in the middle of a meadow and mowing a broad circle around its base. It stands out. Anyone with the wit to look will understand a signal is being broadcast.

Eyecatcher

On either side, the two trees we noted earlier loom eye-catchingly against the sky. Each is exactly the same horizontal distance from the stump. They feel like very much like a pair of pendants that have been symmetrically arranged around a focal point. They’re also connected to the stump via the two hills they occupy. The ridgelines formed by the hills run directly into that solitary stub of tree trunk and terminate there. Every realist painter with an old fashioned eye for design will do a little double-take when they spot this. It’s considered bad practice to allow the contours of separate features to end at a single shared point. Particularly if that terminal happens to be at the precise centre of the painting. It looks unnatural and contrived. Never more so than in a landscape. But Giorgione – an absolute master of naturalism - has broken these rules. When we put this alongside his use of geometry and symmetry, it’s clear the man’s on a mission. He’s determined that the two trees and the stump should be tethered to each other and emphasised to the viewer. Why?

Family Matter

Funnily enough, it doesn’t take much to unscramble what’s going on here. It’s probably best to start with the stump. It’s the latch on the door we want to open. In 16th century Italian, as now, the word for a stump was ceppo. But Italian, like any other language, can allow multiple definitions of a word. If it’s used in a literary sense, ceppo has a meaning closer to what we get from the English words bloodline or stock. This is the connotation Giorgione was after. He used the stump as a cipher for the notion of family. It’s an idea he’d played around with before. In his painting of shepherds paying their respects to the new born Christ, he’d dropped in a stump opposite the Holy Family as a conceptual echo of the two parents and their baby. But this time, he wanted the idea front and centre. It’s no accident he’s situated it just above the productive loins of the mythical matriarch. She was, after all, the source from which Girolamo’s lineage sprang.

Future Branches

The reason the picture addresses these dynastic themes is straightforward. It was commissioned to celebrate Girolamo’s marriage. It belongs to that epithalamic class of paintings we met with earlier. If we turn to the two trees, it’s clear they represent the bride and groom, or, at the very least, the masculine and the feminine. One is elegant, slender and fair. The other is compact, dark and robust. Each curves gently towards the other; perhaps a modest sign of their shared affection. We’ll never know for sure, but it’s possible the settlements on the left and right of the landscape in some sense represent their family homes. The bride leaves hers behind to join her husband at his formidable household, which, as we saw earlier, overflows with divine bounty. Much more definite is the manner in which the pair are brought together and united - via their respective ridgelines - in the concept of family represented by the ceppo. Better yet, fresh shoots emerge from the stump. These are an expression of the children the newlyweds hope to have. And with a supreme procreative goddess presiding over the couple’s union, why wouldn’t they?

Love and Death

Of course, there’s more to the painting than lineage, breeding and the blessings of a divine mother figure. Giorgione’s too poetic to leave things there. It’s also about love and human tragedy. When we look at the bottom left of the picture, we can see four or five tiny yellow blossoms emerging from the grass beneath Venus. These are anemones. In symbolic terms, they’re an easy read. If we turn to another work of Ovid’s which was well-thumbed in 16th century Italy, Metamorphoses, we find the dainty flowers turn up in the story of Venus and Adonis. The relevant passage can be found at the end of book X. It describes the goddess mourning her lover who’s bled to death after a boar has gored him through his crotch. Her grief is so dreadful she sets out to immortalise her devotion to the dead youth. She sprinkles fragrant nectar onto the blood pooled around Adonis. Wherever it falls, within an hour, an anemone springs up. The fragile, short-lived blossom instantly becomes an emblem of love and a poetic reminder that even for the gods nothing - no matter how precious - can last forever. And here the flower is, poking through the grassy canopy underneath the goddess, a signal not only of the love Girolamo shares with his bride, but also its mortal constraints.

All in all, this is the most beautifully arranged metaphor for marriage in western art. Yes, Giorgione’s taken a philosophical bicycle pump to the goddess of love and inflated her into a cosmic mother figure. But he’s joined this idea to the matrimonial theme his patron required so smoothly and with such elegance it’s impossible to find fault. Every touch is subtle yet bang on the button. There’s no flab, no clumsiness, no uncertainty. The only question we might ask is why he chose a view of nature to express ideas we normally think of as belonging to the human realm. But Giorgione was passionate about the natural world. He invented landscape painting more or less single-handedly. He seems to have believed there was a truth and sense of meaning to the rural outdoors that could adequately explain anything. Spend a little time getting to know The Sleeping Venus, as we have, and it’s hard not to agree. How appropriate it is that the picture is the finest he ever managed. And how sad it is that he was dead before the final varnish was brushed over it. This is where Titian re-enters our story.

Most scholars believe that when Giorgione lost his life to the plague, the Sleeping Venus was incomplete. A local Venetian art lover is our source for this interesting snippet. Writing in his journal 15 years after Giorgione’s death, he reports that Titian stepped in to finish things off and make sure that Girolamo got the picture he’d ordered. He then lists the areas by Titian’s hand. These include much of the background, the fabrics underneath Venus, and a cupid at her feet. (The latter was long ago erased by a clumsy restoration effort.) In other words, the received wisdom is that the picture is not far off a fifty-fifty effort shared between two contemporaries.

This is seductive stuff. It unites two titanic talents of the Renaissance on a single canvas. It gratifies a desire identical to that of the football fan who’d give anything to watch a game where Messi and Maradona play in the same XI. Yet there really isn’t any reliable way of verifying the extent of Titian’s involvement. It’s all guesswork. Perhaps he contributed as much as that 16th century connoisseur claimed. It’s a good bet he did less though. For starters, there’s a holistic completeness to the way Venus, the landscape and the matrimonial message have all been integrated. It’s a powerful indication that a single mind was responsible for the design from start to finish, not a bit-by-bit committee. It would also be odd for Titian, if he was responsible for the background, to use nature as such an explicit mouthpiece. This was not his usual MO. And even where X-rays reveal adjustments made to the painting – there are a few – we’ve no overwhelming evidence they came from the brush of anyone other than Giorgione. We must remember, painters are allowed to alter course as they go. This happens so often, in fact, there’s a word for the tweaks and alterations: pentimenti. It’s a lovely sweet sounding tag for those dithering changes of mind, made all the better by its literal meaning: regrets.

The Recycling

Even so, the boffins will point to two subsequent works by Titian, each of which includes a portion of the landscape we can see in Giorgione’s painting. They think it’s unlikely Titian would’ve have repeated these passages in his own pictures if they weren’t originally of his invention. They suggest that having come up with the background imagery for the Sleeping Venus, Titian then recycled it. Partly because it was a good fit with what he was painting at the time, and partly because he wished to subtly lay claim to those elements of Giorgione’s picture that were his. It’s a neat proposition. But it assumes Titian was above the grotty business of borrowing the ideas of others. The truth is, like most formidable talents, the man was laid back about the practice. As we’re about to see, he lifted the reclining nude in the Sleeping Venus in her entirety. There’s no reason to suppose he didn’t do the same with the background. With Giorgione safely in the grave, it’s not as if he was going to receive a knock on the door and an earful of abuse.

There is one scenario, however, where we can be confident Titian’s involvement was more direct. This is a little technical, but bear with it. If the Sleeping Venus wasn’t quite finished when Giorgione died, it would have been without its final varnish. Patches of the painting would have ‘sunk in’. Sinking in is a process where colours lose their glossiness and strength. To a greater or lesser degree, it takes place all through an oil painting’s development. It can only really be stopped with a sturdy layer of varnish. Varnish, however, if used too early, can stuff up how the layers beneath bond to each other, increasing the chance of cracks appearing. It shouldn’t be applied before the painting is sufficiently dried, something which can take anywhere between 3 and 12 months from the last brushstroke. In the meantime, as colours gradually sink in and oxidise, some will turn matte or chalky and lose their lustre. They can end up looking like early stage preparatory layers, rather than the finished article. The rich variety of tone and temperature that’s essential if the image is to look lifelike and three dimensional won’t be there. More likely than not, Giorgione’s painting had a few areas like this when it arrived on Titian’s easel. Before he could varnish and deliver it to Girolamo, Titian would need to go over the trouble spots to check how far along they were when Giorgione died.

The standard solution to this complication, one which Titian undoubtedly used, is to ‘oil out’ the problem areas by brushing on sparse, diluted applications of the medium with which the paints were originally mixed. This generally brings everything roaring back to life. But sometimes it isn’t enough. If the paint isn’t thick enough, a few days later the colours may once again seem flat. The same can happen if the canvas beneath is just a touch too absorbent. When this happens, the next step is to make some subtle adjustments via ‘glazes’ and ‘scumbles’. Thin layers of fresh colour are laid semi-transparently over the old to lend tinting strength and to fine tune the overall appearance. (A glaze is a darker colour laid over a light one, whereas a scumble is the opposite.) This would also be the moment to tidy up any niggling loose ends which hadn’t been articulated fully: a pocket of grass here, a smear of cloud there, and so on. Then, once everything looked correct and the painting had a chance to dry, a satisfying, gloopy coat of varnish would have been brushed over the entire surface to keep the colours permanently glossy. In studios around the world, every day for the six hundred years oil paints have been widespread, realist artists have been busy playing this whack-a-mole game as their paintings enter the final furlong. It’s an unavoidable part of the process. The report we have of Titian’s hand roving all across the canvas fits perfectly with these late stage activities. It’s a far more plausible scenario than one where he painted half the picture from scratch.